- EC Issues Gazette for 297 Newly Elected MPs |

- 9-year-old boy beaten to death over betel nut theft in M’singh |

- BNP fast-tracks cabinet plans after resounding victory |

- Modi Calls Tarique, Pledges India’s Support |

Rohingya Refugees Risk Lives at Sea Amid Camp Hardships

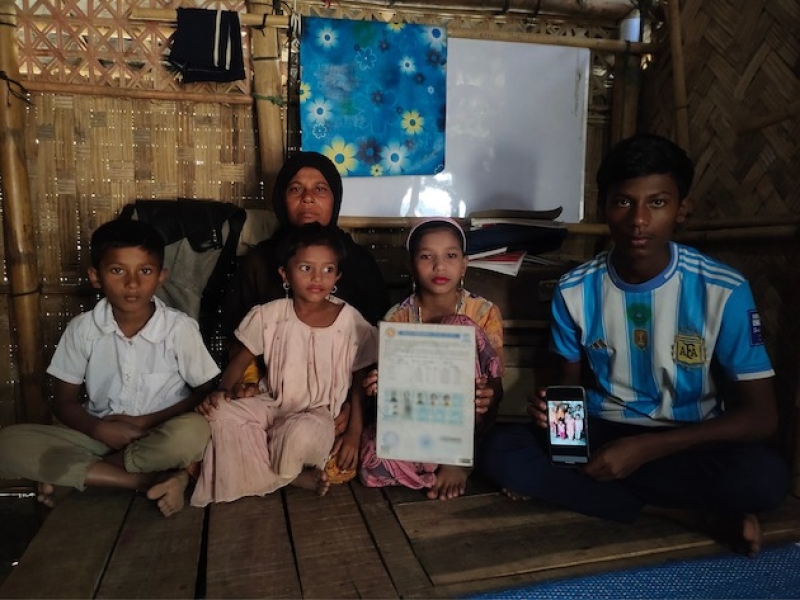

Mon Bahar’s family poses with a photo taken before her husband Rahmot Ullah and daughter Shamsun Nahar, both Rohingya refugees, tried to leave Cox’s Bazar for a better life in Malaysia.

Dawn breaks over the world’s largest refugee camp, and smoke rises from small cooking fires among rows of bamboo and tarpaulin shelters as children queue for food.

For 38-year-old Mon Bahar, one of over 1.1 million Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, mornings are the hardest. She feels the absence of her husband and eldest daughter most acutely.

“We were seven,” she says quietly. “My husband, me, three daughters and two sons.” Now they are five.

After eight years in the camp with few opportunities and little hope, Mon Bahar’s husband, Rahmot Ullah, decided to attempt the dangerous sea journey to Malaysia through traffickers, hoping to earn money to support his family. Their 15-year-old daughter, Shamsun Nahar, insisted on going too.

The family fled the 2017 military crackdown in Rakhine State, Myanmar, which forced over 700,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh. The UN estimates at least 10,000 people were killed.

Mon Bahar recalls worrying for her daughter’s safety in Camp 1 West, where sexual violence against women is common, and for the looming cost of her marriage and dowry. Shamsun Nahar hoped to reach Malaysia to marry without paying a dowry.

The family agreed to pay traffickers 350,000 taka (about USD 2,850) per person after arrival. On 26 October last year, Rahmot Ullah and Shamsun Nahar left the camp.

Eleven days later, Mon Bahar received a call from her husband: their boat had broken down, and they had been drifting at sea for five days before being rescued by Malaysian authorities and NGOs. He was alive but separated from his daughter. Of 303 passengers, 29 bodies were recovered and only 14 survivors identified. Rahmot Ullah survived but was detained; Shamsun Nahar remains missing.

Mon Bahar is left caring for her underage children with no income and no information about her missing family. “I asked UN agencies. No one can tell me anything. We are helpless,” she says.

The UNHCR calls this one of the world’s most complex humanitarian crises, worsened by the 2021 Myanmar military coup. Over 3.68 million people are internally displaced, while 1.5 million refugees are outside the country, mostly in Bangladesh.

From 2022 to 2025, an estimated 23,400 Rohingya attempted the sea journey from Bangladesh and Myanmar, with nearly 10 percent dead or missing. In 2025 alone, 6,200 people attempted the voyage on 153 boats, and 892 were reported dead or missing. Women and children accounted for 60 percent.

Traffickers exploit desperation in overcrowded camps, while naval forces intercept boats and detain both traffickers and refugees. Main destinations include Malaysia and Indonesia, but the routes are increasingly dangerous.

Lilianne Fan, ASEAN advisor on the Myanmar crisis, says the tragedy repeats each sailing season due to political failure rather than lack of knowledge. “For more than a decade, Rohingya families—including women and children—have risked their lives at sea because they see no other pathway to safety or dignity,” she said.

Eighteen-year-old Mohammed Suhail, who fled Myanmar in 2017, reflects the hopelessness many youth feel. “My life is very restricted. No higher education, no job, no freedom of movement. No hope to return,” he says.

Without legal rights to work, refugees depend on aid. Funding cuts, restrictions on movement, and ongoing conflict in Rakhine State worsen desperation. Traffickers exploit this, promising safety and income while many lives are lost at sea.

In Camp 1 West, Mon Bahar sits outside her shelter as evening falls. “We don’t want to die at sea. We want to live with dignity,” she says. Her plea is simple: improve camp conditions so families are not forced into such perilous journeys.