- Islami Andolan to Contest Election Alone in 13th Poll |

- 3 killed in Uttara building fire; 13 rescued |

- Late-night deal ends standoff: BPL resumes Friday |

- Global Marine Protection Treaty Enters into Force |

- US Immigrant Visa Suspension Triggers Concern for Bangladesh |

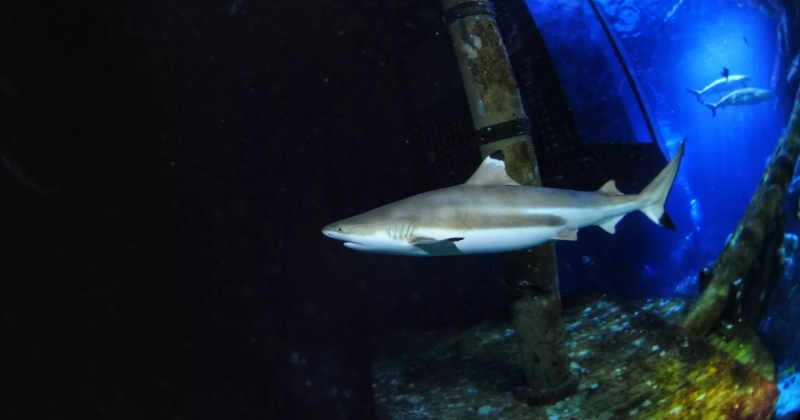

Rising Ocean Acidity May Gradually Weaken Sharks’ Teeth

Sharks, among the ocean’s most formidable predators, depend on their razor-sharp, constantly regrowing teeth for survival. However, scientists warn that rising ocean acidity could slowly weaken these vital weapons, posing a new threat to shark populations.

The warning comes from a study by German researchers who examined how increasing seawater acidity affects shark teeth. Human activities such as burning coal, oil and gas have raised carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, much of which is absorbed by the oceans, making seawater more acidic.

The study found that higher acidity can damage the structure of shark teeth, making them more prone to cracking, corrosion and breakage. Over time, this weakening could undermine sharks’ ability to hunt effectively and threaten their role at the top of the marine food chain.

“The ocean won’t suddenly be filled with toothless sharks,” said lead researcher Maximilian Baum, a marine biologist at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf. “But weaker teeth would add another serious pressure on animals already facing pollution, overfishing, climate change and habitat loss.”

Baum said the team observed clear signs of corrosion on shark teeth, suggesting that the predators’ long-term ecological dominance could be at risk if ocean chemistry continues to change.

The findings were published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science amid growing global concern over ocean acidification. Scientists estimate that if carbon emissions continue at current rates, the ocean could become nearly ten times more acidic by 2300.

For the study, researchers collected more than 600 naturally shed teeth from an aquarium housing blacktip reef sharks, a species found in the Pacific and Indian oceans. The teeth were placed in water reflecting present-day acidity and projected acidity levels for the year 2300.

Teeth exposed to more acidic conditions showed severe damage, including cracks, holes, root corrosion and overall structural degradation. The researchers said these results indicate that ocean acidification could significantly reduce the physical strength of shark teeth.

Shark teeth are highly specialised tools designed for slicing through prey rather than resisting chemical corrosion. Although sharks can grow and lose thousands of teeth over their lifetime, strong teeth remain essential for hunting and maintaining balance in marine ecosystems.

Many shark species are already under serious threat. According to global conservation assessments, more than one-third of all shark species face the risk of extinction.

Commenting on the study, marine scientists not involved in the research said the findings were credible but noted that shark teeth develop within mouth tissue, which may offer some protection from changing ocean chemistry in the short term. Others stressed that while acidification is a growing concern, overfishing remains the greatest immediate threat to sharks worldwide.

Scientists warn that the impact of ocean acidification extends beyond sharks. Shellfish such as oysters and clams may struggle to form shells, while fish scales could become weaker and more brittle.

Baum cautioned that ocean acidification should not be overlooked as a long-term danger to sharks, particularly for species already close to extinction.

“The evolutionary success of sharks depends on their perfectly adapted teeth,” he said.