- CA Yunus pays homage to Liberation War martyrs on Victory Day |

- Bangladesh capital market extends losing streak for second day |

- Bangladesh celebrates Victory Day Tuesday |

- 'Different govts presented history based on their own ideologies': JU VC |

Navigating the Humanitarian Dilemma in Rakhine

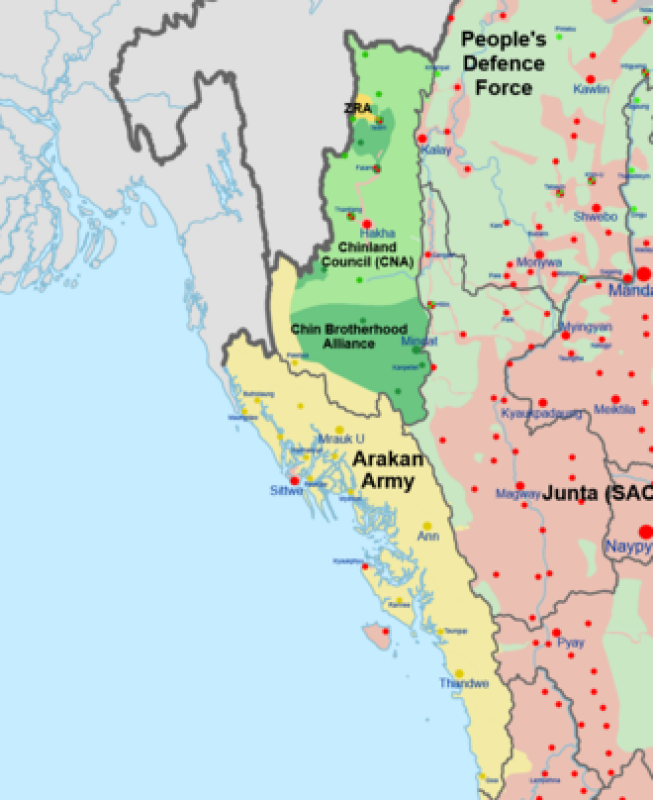

Rakhine State of Myanmar. Wikipedia

Mostafa Kamal Majumder

The international spotlight is once again on Myanmar’s Rakhine State, where the conflict-ridden region faces a deepening humanitarian crisis. As famine and food insecurity escalate, the United Nations has proposed the establishment of a humanitarian corridor to deliver essential aid to the beleaguered civilian population. While this move appears necessary on humanitarian grounds, it has triggered concern in neighboring Bangladesh—particularly in relation to the complex interplay of regional security, Rohingya repatriation, and geopolitical signaling.

At the heart of this controversy lies the shifting control of Rakhine territory. Much of the region is now under the effective control of the Arakan Army (AA), an ethnic Rakhine armed group engaged in prolonged conflict with Myanmar’s military junta. While the AA's narrative has long centered around autonomy and resistance against central oppression, its treatment of the Rohingya Muslim minority remains deeply suspect. Accusations have emerged from multiple quarters, including human rights groups and regional actors, that the AA, like the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Army), harbours deep-seated prejudice against the Rohingya and may not be a reliable conduit for aid with impartial access.

Bangladesh’s apprehensions are understandable. Hosting over a million Rohingya refugees in sprawling camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh has consistently urged international pressure on Myanmar to ensure safe, voluntary, and dignified repatriation. Dhaka fears that routing aid through the Arakan Army may lend it de facto legitimacy, further complicating the dynamics of eventual repatriation. More critically, any such move risks antagonizing the Myanmar junta, who may interpret it as an erosion of sovereignty and react by further hardening their stance on repatriation negotiations or even stepping up military operations in the region.

Yet, from a humanitarian perspective, the case for a corridor is compelling. With the Myanmar military continuing its brutal campaign and aid blockades worsening, Rakhine’s civilian population—Rakhine Buddhists, Rohingya Muslims, and others—face a catastrophic situation. Starvation does not differentiate between ethnicities or political affiliations. A functioning aid corridor could be a lifeline for hundreds of thousands, and any delay in delivering food and medicine could exact a deadly toll.

This is a moment that calls for nuanced diplomacy rather than outright rejection or uncritical approval. The UN and international stakeholders must ensure that any humanitarian access is guided by strict principles of neutrality, impartiality, and accountability. Aid must reach all communities, including the Rohingya, and should not be used to strengthen armed factions or entrench discriminatory power structures. Clear monitoring mechanisms, possibly involving third-party oversight or UN peace presence, should be part of any corridor framework.

For Bangladesh, the imperative lies in balancing principled humanitarianism with pragmatic national interest. Dhaka should actively engage with the UN to shape the terms of aid delivery rather than oppose it outright. It must also lobby for simultaneous pressure on Myanmar’s junta to recommit to a repatriation process with international guarantees. Meanwhile, the international community must not lose sight of the root causes of this crisis: the systematic disenfranchisement and persecution of the Rohingya and the broader collapse of democratic governance in Myanmar.

Granting a humanitarian corridor should not be viewed as a zero-sum game between ethics and politics. Instead, it must become a platform to reassert international engagement in Myanmar’s forgotten war and to remind all actors—including the Arakan Army—that access to aid comes with the obligation to uphold human dignity, not subvert it.