- 11-Year Run of Record Global Heat Continues: UN Agency |

- Gaza Ceasefire Not Enough as Children Continue to Die |

- Bangladesh Sets Guinness Record With 54 Flags Aloft |

- Gambia Tells UN Court Myanmar Turned Rohingya Lives Hell |

- U.S. Embassy Dhaka Welcomes Ambassador-Designate Brent T. Christensen |

UN Air Service Keeps Lifeline Open Amid Funding Strain

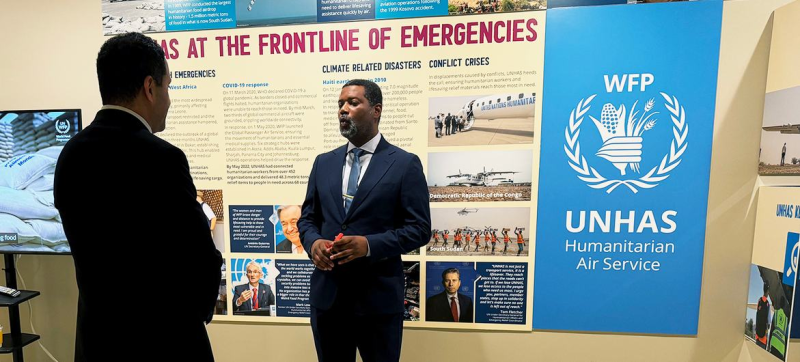

Hedley Tah (right), Head of External Relations for UN Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS), speaks with UN News.

For George Stroumboulopoulos, the only way to reach an inaccessible destination near the border of Chad in 2004 was to fly on a UN Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) plane. It was the first time he had ever heard of the service.

“I just watched how it was a central driver for humanitarian agencies from all over – not just the UN – and it was the only organisation that could do that,” said Stroumboulopoulos, an actor, media interviewer and producer, who now serves as an Ambassador for the World Food Programme (WFP), which runs the lifesaving service.

For two decades, UNHAS has provided vital air links that allow UN agencies and their partners to deliver aid and deploy humanitarian workers to some of the world’s most hard-to-reach regions.

From the COVID-19 pandemic – when commercial flights were grounded – to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the service has kept going under some of the most challenging circumstances imaginable.

But with less funding available, UNHAS flights and the resources they transport are now at risk.

“What we are trying to do is get political support from Member States, reminding them of the promise of leaving no one behind. It is crucial to keep funding UNHAS,” said Hedley Tah, head of external relations for the service, speaking at a pop-up exhibit during the UN’s high-level week in New York.

Identifying and fixing inefficiencies is one of the goals of the UN80 Initiative, the system-wide reform plan rolled out earlier this year by Secretary-General António Guterres.

UNHAS, however, is already considered highly efficient, according to Mr. Tah. The centralised service is used by over 600 organisations, sparing them the cost of setting up or maintaining their own aviation systems.

“We are able to do that for the entire humanitarian community,” he said. “This allows other organisations to focus on their mandates while we manage the supply chain.”

He noted that 70 per cent of humanitarian aid costs are linked to supply chains, such as flights and distribution. “Even a small percentage of cost savings in the supply chain can translate into hundreds of millions of dollars in savings — and that’s where UNHAS comes in.”

Compared to last year, UNHAS has 50 per cent less funding to continue its operations.

“That affects our ability to respond to humanitarian needs,” said Mr. Tah. “But nonetheless, we are now doing more with less.”

To remain effective despite financial constraints, the service has reduced the number of aircraft and renegotiated contracts. While some destinations are no longer served, UNHAS still operates in 21 countries.

According to the WFP UNHAS Annual Review, its 2028 aviation strategy includes improving fleet readiness, strengthening emergency deployment mechanisms, and upgrading digital booking systems.

“The kind of expertise required to achieve what UNHAS does is unparalleled,” said Stroumboulopoulos, who flew with the service in Syria last year.

“I cannot imagine the level of pain, loss of life, dignity, and hope that would follow if UNHAS did not exist.”